How could we have resisted spying on our new neighbors? Upon their arrival, they would sing by our windows and occasionally tap on the glass. Soon the couples expanded their families, turning each home into a mosh pit of hungry, but oddly cute, ragamuffins. At some point, we came up with nicknames for them (but more about those later).

Our new neighbors were house finches, and they had built nests inside two awnings. During the past few weeks, we had been checking in on them. Not only did the nests afford us the opportunity to intimately watch these birds give rise to a new generation, but we were able to further ponder how a species native to the western parts of North America, especially Mexico,1 had come to call North Carolina and the rest of the eastern United States home. Common today in all fifty states, this bird has a rather remarkable story.

From Tinseltown to Gotham

When Americans settled westward during the nineteenth century, they took a fancy to house finches. As many people today know, these birds love to build nests along human dwellings, which means that trapping them would have been relatively easy, likely resulting in part to their being sold as caged songbirds. Once captured, the creatures could be transported to other places—and indeed they often were. By the 1880s, American travelers had introduced house finches to the Hawaiian Islands.2, 3

In 1918, the Migratory Bird Treaty Act banned the human trafficking and sale of house finches. However, the practice continued for decades in the United States. The caged birds were even dubbed “Hollywood finches” by illegal bird traders so as to glamorize the species, making it more exotic and attractive to potential buyers. The “Hollywood” part of the name was a promotional gimmick, for the finches are native to the West Coast but also to other western states, not just Tinseltown and surrounding areas of California.4

As late as 1940, “Hollywood finches” were being sold in New York City. Increased enforcement, though, eventually ended the illegal sale of the birds—but with unintended consequences. Fearing visits by authorities, traders and pet shops ended up releasing their caged house finches into the wild. Eyewitness reports of the birds began circulating in New York City but quickly radiated out to neighboring states.5, 6 Today, house finches are found from northern Florida up to southern parts of Canada, but their rapid expansion has come at a cost.

“Moldies” and “Andies”

Our recent neighbors are likely descendants of those birds released in New York City over seventy-five years ago. In most cases, each clutch gave rise to four youngsters. Covered partially in spots of down, the new hatchlings were not much to look at. My wife jokingly likened their appearance to moldy strawberries. But these hungry creatures quickly grew, sprouting other feathers. By the time the fledglings left their nest, the only visible sign of their down was several unruly sprigs above their eyes, a characteristic reminiscent of the brow hair sported by the late 60 Minutes commentator Andy Rooney.

To differentiate the birds’ stages, my wife and I often made tongue-and-cheek references to them as “Moldies” and “Andies.” They grew up fast! In a matter of days, the Moldies became Andies. And, boy, did those ravenous bushy-eyed juveniles keep their parents busy. The last of them, though, took wing a couple days ago. For now, our spying eyes have returned to the bird feeders.

Sources:

- Mexico’s connection to the bird is reflected in the species’ scientific name, Haemorhous mexicanus.

- Hill, GE. A Red Bird in a Brown Bag: The Function and Evolution of Colorful Plumage in the House Finch. New York: Oxford University Press, 2002. pp. 21, 224.

- Grinnel, J. “The Linnet of the Hawaiian Islands: A Problem in Speciation.” University of California publications in zoology. The University Press. Vol. 7, No. 4 (1911), pp. 179–195.

- Hill, GE. pp. 21, 221–222.

- Elliott, JJ, Arbib, RS. “Origin and Status of the House Finch in the Eastern United States,” The Auk. Vol. 70, No. 1 (Jan., 1953), pp. 31–37.

- Hill, GE. pp. 222–223.

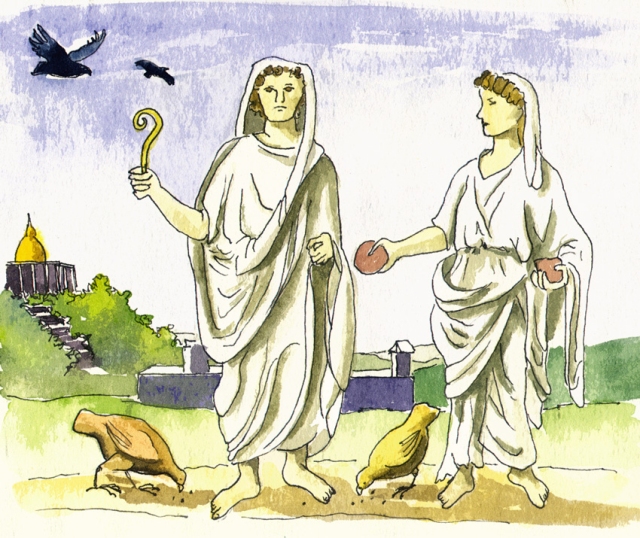

Patterns exist throughout nature. For people ages ago, such things were considered messages from the gods. Decoding these encrypted communications was at the heart of ancient divination, a common practice of early civilizations.

Patterns exist throughout nature. For people ages ago, such things were considered messages from the gods. Decoding these encrypted communications was at the heart of ancient divination, a common practice of early civilizations.