Chances are you’ve never glimpsed an albatross in the wild. What you likely know about this bird instead persists from other sources, namely Samuel Taylor Coleridge’s “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” a widely influential poem based loosely on a historical maritime event.

One of Literature’s Greatest Symbols

Perhaps no bird resonates more as a literary symbol than the albatross. Since these creatures spend the majority of their time at sea, people rarely see them. The same cannot be said of crows, ravens, owls, and hawks—birds with a rich symbolic tradition as well—but who are far from elusive. The scarcity of sightings is undoubtedly a contributing factor to the albatross’s enduring mystique.

For many of us, at least in Europe and North America, the thought of this sea bird instantly conjures associations with Coleridge’s famous late eighteenth-century poem. Again, this may be due to the fact that many of us don’t have opportunities to see an albatross for ourselves outside of photographs and documentary films. Oddly enough, even the poet who impacted the way so many people view this creature today never actually saw one! (1, 2)

Yet Coleridge’s poem has continued to shape our cultural view of the albatross as a benign emblem of nature transgressed. Not surprisingly, we come across references and allusions to the British Romantic poet’s albatross later in other major literary works, such as Herman Melville’s Moby-Dick and D.H. Lawrence’s poem “Snake” (3). Coleridge’s albatross, thus, remains larger than life, continuing to live on in our collective imagination. Yet it’s also a symbol as relevant today, if not more so, than when first introduced over two centuries ago.

The Poet’s Cautionary Tale

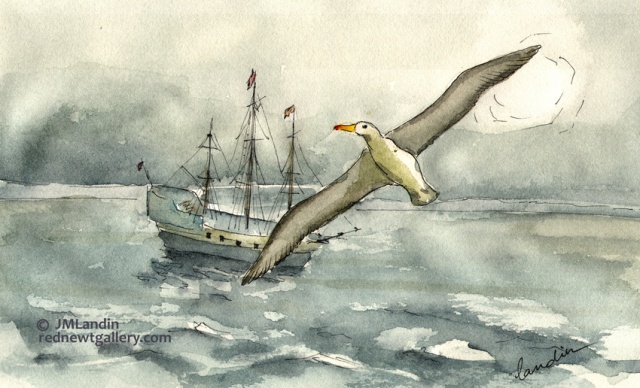

The power of “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” lies in how it exists as an amalgam of so many things. A story within a story about a sailor’s incredible journey, the poem takes the reader back in time with its archaic language to a cold, remote location near Antarctica. There, in narrative verse evocative of a ballad, we encounter superstition and haunting supernatural imagery, punctuated with a strong moral made possible by a bird metaphor.

After weeks of suffering through a storm, the ancient mariner and his crew spot an albatross through the fog. Its appearance strangely coincides with the dense clouds of smoke-like vapor. Welcomed for days by the sailors with “food and play,” the bird lingers along with the ship. However, as the troublesome fog endures, the old grey-bearded sailor eventually grows exasperated. Blaming the albatross for the horrible weather conditions, he decides to take down the bird with his crossbow. Unknowingly with this act, the mariner unleashes problems unlike any encountered before.

The old man of the sea may have been right about the albatross’s link to the fog, but he didn’t anticipate that the creature was also responsible somehow for the breeze that once filled his ship’s sails. As the winds stall, the crew’s morale falters. The sailors eventually turn on the ancient mariner (“what evil looks / Had I from old and young”), as if forcing him to wear the slain bird (“Instead of the Cross the Albatross / About my neck was hung”) (4, 5). And later, plagues ensue. Only after a change of heart towards other non-human forms of life around him and many, many travails at sea, does redemption at last come. But such salvation has its limits, for that same change of heart must also occur in all of humanity—the reason why the mariner continues to share his story.

Coleridge’s message is quite clear. Any reader could easily take his poem as an environmental cautionary tale: be warned that tampering with nature for a small group’s narrow-minded, selfish interests can provoke unintended consequences.

Based on an Actual Event?

One important source of inspiration for Coleridge included the account of Captain George Shelvocke’s early eighteenth-century global expedition, a long voyage beset with numerous problems. Early on, Shelvocke’s ship, the Speedwell, was separated during a storm from his larger companion vessel. By the time the skipper’s vessel had advanced beyond the Le Mair Strait, near the southern tip of South America and not far from the Antarctic Peninsula, the crew faced a horde of challenges: frigid temperatures, harsh tempests, and a lack of available fish (6).

At this point, Shelvocke recounts how his second captain, Simon Hatley, decided to shoot a black albatross. This poor lone bird had been deemed an omen, targeted for both its color and hovering by the ship for several days (7). Interestingly, Hatley seemed to have a propensity for taking to the seas on voyages that somehow would later inspire major works of literature. The Guardian’s Vanessa Thorpe notes from Robert Fowke’s The Real Ancient Mariner, a biography of Hatley, that the sailor oddly enough also had connections to Daniel Defoe’s Robinson Crusoe and Jonathan Swift’s Gulliver’s Travels (8).

Although “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” came later—in 1798 as part of Lyrical Ballads, a collection of verse from both Coleridge and his friend William Wordsworth—Hatley’s role in the poem was more crucial than in those earlier works by Swift and Defoe. Also, Wordsworth, who had been recently reading Shelvocke’s account, seems to have been the one to have suggested the incident to Coleridge during one of their walks (9). As ornithologists Roger Lederer and Noah Strycker have noted, Coleridge never encountered a living albatross (10, 11). It’s ironic that the poet, perhaps best known for his connection primarily to this one particular bird, never actually got to see his subject gliding in all its glory over the ocean.

“A Sadder and a Wiser Man”

Due to the popularity of “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner,” many people today think that killing an albatross was universally considered bad luck by sailors, a surefire way to curse your voyage. But this was definitely not the case. For some seafarers, yes, harming an albatross was taboo. For others, though, killing these birds was far from prohibited, as demonstrated by Shelvocke’s account, and also by the 1857 French poem “L’Albatros” (“The Albatross”) by Charles Baudelaire. Reasons for taking down these birds included superstition, but also practical matters, as their meat could be eaten, certain bones could be made into stems for smoking pipes, and their foot webbings could be turned into tobacco pouches (12, 13). With one poem, Coleridge eventually revamped the general public’s perception of this elusive bird and our relationship with it.

In his book Birds in Literature, scholar Leonard Lutwack discusses the popular theme involving the “wanton killing of sacramental or totemic animals” and the “atonement” necessary for this aggression against nature (14). It’s a motif that occurs in several works about birds, in plays such as Henrik Ibsen’s The Wild Duck and Anton Chekhov’s Seagull, as well as in other poems such as Robert Penn Warren’s “Red-Tail Hawk and the Pyre of Youth” and Gwen Harwood’s “Father and Child” (15). Lutwack notes all of these and more, including several works by Coleridge that revisit the theme most poignantly expressed in “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.”

“Both Coleridge and Melville,” Lutwack explains, “are stating the ecological principle that our survival depends on our recognition of the worth and interrelatedness of all living things” (16). That message, as many of us continue to discover, is one of growing significance in a world with the decline and disappearance of many species. Fortunately, the albatross is still around today, and lives as a poetic reminder that not only conservationists—but all of us—have lots more work to do.

Sources:

- Lederer, R. Amazing Birds: A Treasury of Facts and Trivia about the Avian World. London: Quarto Publishing, 2007. p. 13.

- Strycker, N. The Thing with Feathers: The Surprising Lives of Birds and What They Reveal About Being Human. New York: Riverhead Books, 2014. p. 259.

- Lutwack, L. Birds in Literature. Gainesville, FL: University Press of Florida, 1994. pp. 178, 180–181.

- Coleridge, S.T. “The Rime of the Ancyent Marinere.” Wordsworth, W., Coleridge, S.T., Owen, W.J.B. (editor). Lyrical Ballads. Second Ed. New York: Oxford University Press, 1969. pp. 7–32.

- Coleridge, S.T. “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner.” The Literature Network, Jalic Inc.: http://www.online-literature.com/coleridge/646/.

- Shelvocke, G. A Voyage Round the World by the Way of the Great South Sea: Performed in a Private Expedition during the War, which broke out with Spain, in the Year 1718. Second Edition. London: Printed for W. Innys and J. Richardson, M & T Longman, 1757, pp. 75–76.

- Shelvocke, G. pp. 75–76.

- Thorpe, V. “Uncovered: the man behind Coleridge’s Ancient Mariner,” 1/30/2010. The Guardian: http://www.theguardian.com/books/2010/jan/31/man-behind-coleridges-ancient-mariner.

- Coleridge, S.T. p. 135.

- Lederer, R. p. 13.

- Strycker, N. p. 259.

- Barwell, G. Albatross. London: Reaktion Books Ltd., 2014. pp. 59, 95–96.

- Armstrong, E.A. The New Naturalist: A Survey of British Natural History – The Folklore of Birds: An Enquiry into the Origin & Distribution of Some Magico-Religious Traditions. London: Willmer Brothers & Haram Ltd., Birkenhead for Collins Clear-Type Press, 1958. p. 214.

- Lutwack, L. pp. 177–178.

- Lutwack, L. pp. 181–186.

- Lutwack, L. p. 180.

Excellent!

Thanks!

Excellent post!… Baudelaire’s poem is absolutely beautiful, even more if we read it in french!.

All my best wishes. Aquileana 😀

Thanks! Baudelaire’s “Les Fleurs du mal” is a classic! Fortunately, my copy has the original French along with English translations. By the way, let me know when you post about the Phoenix, and I will link to your site. (I don’t plan to do anything related wholly to the mythological bird, but will include it as an aside to other topics.) Best wishes to you as well!

I´ll let you know…. By the way, I´ll add a pingback to your post on mythological birds … i.e eagle on my next post… It will be just a brief mention… But well, I wanted to let you know in advance!.

all the best to you. Aquileana 😀

Ok, that sounds good. I’ll be looking out for your next post. Thanks, Aquileana!

Stirs undergrad memories. Love the illustrations; have you come across this site … http://albatross.org.nz/ ?

No, I haven’t seen that website before. Very cool! Now my wife and I have another reason to visit New Zealand. Thanks so much! I’ll pass along your kinds words about her illustrations. Take care!

Interesting post :-). You’ve inspired me to think about reading “The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” again. I’m pretty sure I read it in high school, but I have no recollection of it and I’m fairly certain I didn’t appreciate it much back then. I read Noah Strycker’s book recently and found it quite beautiful. It was one of those books on a special display shelf at the library. The title peaked my interest. The part about the albatrosses was my favorite.

I have a vague recollection of watching “The Rescuers” when I was a kid. I remember the albatross being goofy so I always assumed albatrosses were goofy. Haha! Based on a Disney movie! However, I did recently watch an episode of BBC’s The Life of Birds and the albatross had a comically clumsy landing. I guess it is because they don’t land on land much.

It is interesting that an albatross, though real, is essentially a mythical bird for most people. I wonder if I will ever see one… Have you seen one?

Your wife’s illustration is beautiful.

Unfortunately, I still haven’t seen an albatross yet. But I’d definitely like to!

“The Rime of the Ancient Mariner” made a stronger impression on me years after first encountering it. As a young reader, I viewed the writing style with its contrived archaic spellings as well as the story-within-a-story framing as annoying. During my most recent reading, though, these were not obstacles. The descriptions of plagues visited upon the Mariner are quite vivid (e.g., “The Death-fires danc’d at night; The Water, like a witch’s oils, Burnt green and blue and white.”). Of course, the poem is somewhat lengthy, so you may enjoy it more by reading it over several days. Also, I’m glad you found Strycker’s book — I really valued the way he discussed similarities between birds and humans. BTW, I really enjoyed your photos of ducklings during your recent lake outing!

Thank you for appreciating my photos :-). I may follow your advice and read the poem in sections. The rhyming is quite lovely but a few of the archaic words need looking up.

Make sure that you find a version with footnotes. Contextual information and explanations are insightful to fully appreciating this masterpiece.

Interesting article and stunning illustration. I was looking for ideas to style a tattoo recalling the albatross symbolism, longtime obsession of mine, and when I saw this picture on google image it was love at first sight. It was amazing to find it accompanying great food for thoughts. Many thanks to both, the artist and the writer.

Thank you! That was a fun post to do, a good mix of literature, history, and folklore. I passed on to my wife your comments about her artwork. Good luck on the tattoo, and happy New Year!